Playing for Life

By Jeannie Gagné and Neil Olmstead

This practical advice for singers and pianists can help prevent injuries and foster healthy technique.

|

|

| Associate Professor of Voice Jeannie Gagné is a seasoned performer, writer, and educator. Visit www.jeanniegagne.com or www.soundation.org. | |

| Phil Farnsworth | |

Diagrams of hand and arm |

|

|

|

|

As greater demands are placed upon today's vocalists and instrumentalists, physical injuries have become more prevalent. The ability to deliver a diverse repertoire ranging from Mozart to Bird to Aretha and the need for improvisational skills in various styles and ensemble settings often take precedence over a healthful, noninjurious technique. Indeed, many musicians may consider a slight ache or pain normal until it becomes unbearable or, worse, threatens to halt a career.

Music schools and conservatories have long been a hotbed of student injuries from overuse or improper technique. In a 2000 survey of college music students, 87 percent experienced instrument-related injury. In a 2009 study of 330 university freshmen, 79 percent reported a history of playing-related pain. Berklee-trained musicians encounter the same issues. Conducted in April 2009, a survey of nearly 400 Berklee students found that 78 percent reported pain, numbness, or discomfort while practicing or performing on their instrument.

For some professional musicians, injuries have disrupted or ended careers. Many famous vocalists have experienced significant vocal damage or loss of range after pushing to sing through strain and fatigue. A growing awareness of the problem has inspired a cultural and academic shift toward promoting healthy instrumental and vocal technique and practice. Ideally, musicians should be able to play and sing injury free for life.

Contributing Factors

Tendonitis, carpal tunnel syndrome, vocal strain or damage, shoulder pain, and other maladies can result from repertoire and music style choices, lack of training, the pressures of professional life, and more. Violinist Melissa Howe, the chair of Berklee's String Department, reports that lack of training in basic body mechanics and poor posture led her to suffer from tendonitis and neck and shoulder pain. During the first semester of her undergraduate studies, she was told to play only open strings to experience the sensation of playing free of tension and with good tone. Associate Professor of Guitar Dave Tronzo observes that inconsistent practice routine and poor basic technique are major contributors to injuries. Professional classical musicians cite the abundance of music they learn and insufficient time to warm up, cool down, sleep, and eat as contributors to pain and discomfort while playing.

Even trained singers know how to sing but don't always understand how the voice functions anatomically; such knowledge is not typically part of vocal training. The result is often confusion about how to breathe effectively or place the voice and sing in contemporary styles with healthy technique.

Healthy technique engages the whole body, not just isolated muscles. Body map specialist and guitarist Gerald Harsher suggests that the whole body moves when we make music. Frederick Chopin's quote "Have the body supple right to the tips of the toes," also advocates whole-body awareness. Voice Professor Kathryn Wright reminds us that in singing, there should always be movement, allowing body energy to flow with every phrase.

Alignment and Connectivity for Pianists

Jazz pianist Bill Evans said that the accumulated discipline of knowing how to make his mind, hands, and feet respond would simply take over and allow - even cause - the flow of musical ideas. Renowned for his tone production and revelatory harmonies, Evans made the connection between his hands and his feet. His whole body contributed to his playing.

Pianists who have an understanding of how the skeletal structure-including the hips, spine, and forearm-contribute to the playing process have an advantage in noninjurious playing. Vocalists who sing with an athletic approach to breath support but are also relaxed so the notes are not forced can maintain a healthy voice for years.

The human skeleton is designed to function efficiently, effortlessly, and painlessly as it moves in concert with the pull of gravity. It's a marvelous mobile support system that produces connectivity throughout the body when properly aligned. Avoiding injury at the piano is greatly assisted by consciously working within the coordinated action of this mobile framework. Pianists who take this approach often have solid technique and fine tone.

The flat piano keyboard requires our skeletal structure to move in an aligned and balanced swing. Body alignment does not necessarily indicate straight lines, but rather a response and regulation of the symmetry of the body, a sense of the plumb line of gravity.

The Alexander Technique suggests that alignment can be achieved by moving the head upward and away from the body and allowing the entire body to lengthen by following that upward direction. Tai chi chuan teaches the practice of lifting the back of the head as if it were suspended from a string to naturally align the spine to create alignment. If done without tension or force, a player should feel greater freedom.

Maintaining awareness of alignment increases support of the skeletal structure and can help us eliminate unnecessary motions, such as a foot-stomping habit. According to Isaac Newton, for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction. The body absorbs any jerking motion. Forcing a part of the body to constantly absorb downward shocks has a negative physical impact over time and can create hand, forearm, or shoulder pain. If you find yourself moving extraneously, bring your feet under you as though you were going to rise off the bench a bit. This enables your skeletal arch to be reconnected to the floor and the keyboard, and extraneous motions should be eliminated.

The Spine Leads Melody

The mobile skeletal arch beginning at your feet connects to the melody via the spine that supports your shoulders, arms, and hands up and down the keyboard. Play a multi-octave ascending scale while swinging the body to the right starting from the floor. Sense your arm and hand being carried by the torso as it swings on the bench. Ideally, the melody line - whether improvised or composed - is connected from your feet to the sit bones of the pelvis through your spine that links your shoulders, arms, and hands with the keyboard. This skeletal connection helps support the hands.

Hand and forearm injuries occur when the small bones and joints of the fingers must support arm, shoulder, and torso weight while the hands move intricately along the keyboard. They become the support and workhorse for playing. But an engaged skeletal alignment solves the issue of bearing weight; it becomes fully supported by the floor and the bench, thereby freeing the skeletal levers to move from their respective fulcrums.

The Knuckle Circle

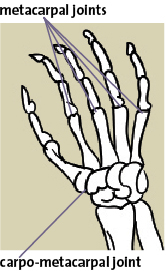

The misconception that our fingers should move only up and down can create hand injuries. We all know how unpleasant stop-and-go driving is. Similarly, a finger that only goes up and down stops and starts with every note played. Angular movement is inefficient and awkward. Pianists often overlook a physical trait that can work to their advantage in preventing injury: the large hand knuckles (metacarpals) are rounded. These knuckles are the primary playing mechanism, and their roundness assists in the lateral movement of the finger from key to key. Our fingers are designed to move in a circular motion, not just up and down. Hence, we can twirl each finger from the knuckle joints.

Sounding each note at the bottom of a circle results in a lateral transfer of balance between tones and yields a deeper legato as well as a rich, powerful tone quality. Ascending passages require a clockwise knuckle circle, and descending pitches require a counterclockwise circle. This action also softens the musculature of the hand, enhancing the flexibility of the joints and reducing forearm tension.

Pulling the fingertip back while playing can create tension and pain in the forearm. Observe the tension by laying your hand flat on a table and pulling and pushing your fingertips back and forth. If the finger operates primarily from a rotating hand knuckle, tension is eliminated.

Passing the thumb under the other fingers in melodic passages presents a particular challenge for pianists. The thumb has three bones, with the largest (the carpometacarpal) being closest to the wrist, from which it rotates in concert with the forearm rotation. Pianists that squeeze their thumb under the hand without rotating the forearm are candidates for extensor tendon strain. Rotating the thumb and forearm in a coordinated circular action offers greater freedom.

Look at the thumb in relation to the forearm. Notice that it appears as an extension of the radius bone. The radioulnar joint (at the elbow) is the fulcrum from which the forearm pivots, playing a distinct role in carrying the thumb.

Play an ascending B-major arpeggio with the right hand. Keep the thumb from squeezing under the hand; instead, rotate it clockwise from the carpometacarpal joint assisted by a clockwise rotation of the forearm from the radial ulna joint. The thumb will be ready to play the next B as the forearm swings back to its neutral position. The thumb is carried octave to octave by the forearm rotation, while the hand is led by the spine that swings from the sits bones on the bench and the feet on the floor.

A pianist who practices with attention to the skeletal alignment of the body-from the feet to the sit bones to the forearm to the hand knuckle and key-has a lower risk of injury, a facile technique, and rich tone.

| Wings Breathing exercise for vocalists | |

|

|

| Inhale: with relaxed shoulders, spread arms outward with full intake of air, let your ribs expand | |

|

|

| Exhale: bring arms slowly together in front of you, sending the breath forward without squeezing it out |

Healthy and Sustainable Singing

When the voice and body are well cared for, the ability to sing can last a lifetime. Voice longevity can be achieved by adapting to daily changes in the body: the instrument you sang with effortlessly yesterday may be different today. Once you know your limits, you can understand when to push and when not to.

As with learning a language, we learn to sing by imitation. Unfortunately, not everything that's popular is healthy or sustainable. That hip, edgy rock quality is frequently the sound of a damaged voice and a short career. And today's recording standards alter the sound of the natural voice, and the use of pitch correction is like air-brushing a fashion model's picture to superhuman perfection. Current technology can create confusion for the popular singer. How can you nail the style you're after if you compare yourself to something unnatural?

The good news is that maintaining healthy technique can produce satisfying results - especially if you're willing to sound like yourself. The contemporary singer is an interpreter and improviser, and audiences respond best to a singer's uniqueness. Observing this principle helps on days when your voice is less physically responsive than you'd like.

Your Invisible instrument

Good vocal technique engages more than your throat or diaphragm muscle. Your voice is an active integration of three systems: air supply (lungs, diaphragm, ribs), tone generator (vocal folds in the larynx), and resonators (mouth, tongue, head, and chest). The larynx is a complex array of ligaments, muscle, and tissue in the neck. It's most important function is respiration, which we cannot control directly. Singing or even speaking is secondary to maintaining life through respiration.

The vocal folds are tiny membranes that oscillate together with air pressure from the breath, in superfast, small puffs. When the vocal folds are closed, the breath is held. On inspiration, the folds open. Learning to control your breath is important for developing power and flexibility. The voice resonates in the throat, mouth, head, and chest to pick up tone and volume, and make each voice unique. The tongue and soft palate are part of the adjustable mechanism, enabling us to form vowels and create the singer's tone.

Author and voice teacher Mark Baxter explains that singing begins with electric brain impulses that cause muscles to contract or relax. Some emotions can compromise your singing by sending contradictory signals to the muscles. "A tremble in your voice means one side of the brain is saying, 'Go ahead and sing,' and the other is saying, 'Maybe you'd better not,'" Baxter writes. "The muscles can't make a decision about which is correct, so they react to both signals." 4

Challenging yourself to sing a difficult riff that you aren't sure you can execute sends contradictory signals from the brain to the voice. These signals make the voice tense and can cause strain.

Building consistent thought patterns that guide fine laryngeal motor control help make your singing reliable. Observe your values about singing so your natural voice and desired style are not at odds. This builds confidence, which helps reduce performance anxiety. Don't be afraid to change a song's key. Work as a team with the band so you're not fighting the PA. Let your singing work for you.

Know Your Limits

Become aware of your limits; never practice through strain or fatigue. If you are under the weather, do gentle humming exercises throughout the day to keep your voice warm. Singing soft, clean tones is a good warm-up and useful for checking your voice's health, even when preparing for powerful singing. Stay hydrated. Relaxing the neck muscles isolates the larynx to enable sound to project through it as though it were a cylinder. Allow your body to move while you sing, rather than stiffening the muscles to control your breath.

| Footnotes

1. Shannon McCready and Denise Reid, "The Experience of Occupational Disruption among Student Musicians," Medical Problems of Performing Artists Journal, vol. 22 no.4, December 2007, 140. 2. Alice G. Brandfonbrener, "History of Playing-Related Pain in 330 University Freshman Music Students," Medical Problems of Performing Artists Journal, vol. 24 no. 1,30. 3. From a 1965 interview with John Mehegan included in the liner notes of The Complete Riverside Recordings by Bill Evans, Riverside Records, 1987. 4. Mark Baxter, The Rock 'n' Roll Singer's Survival Manual. Milwaukee: Hal Leonard Corporation, 1990, 100. |

Jittery nerves undermine technique. To counteract the adrenaline flow, slow your breathing down. Listening to your thoughts as though you are an outside observer helps identify why you are tense. Is there a judge and jury in your mind? Focus on positive thoughts to replace negative ones.

Distractions are also a normal part of performing and can throw you off. People talking, the piano sounding different, or a look from someone in the audience can throw off your game. You might tense up and tighten your throat or forget the lyrics. When you practice a song, visualize how to manage distractions in performance. Do you know the tune inside out? Have a friend talk to you in the middle of the bridge and see whether you can continue. Start your song from the second line of the second verse instead of from the beginning. Practice a cappella. Can you hear the chords and groove in your mind? If your internal dialogue is supportive and manages whatever comes up, you will stay relaxed.

By letting your personal energy rise up and sharing your joy of making music, you access a personal magnetism that all strong performers possess. Vocal health relies on this type of energy and focus. At its best, singing is a dynamic, holistic process that makes you-and your audience-feel great.

Editor's note: Both Gagné and Olmstead will make presentations at the Performing Arts Medicine Association Conference at Berklee on March 28. Visit www.artsmed.org/index.html for details.

Professor of Piano Neil Olmstead author of Solo Jazz Piano, The Linear Approach. Contact him at nolmstead@berklee.edu.