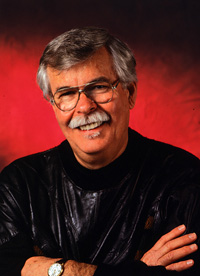

Herb Pomeroy 1930-2007: Beyond Category

|

|

| Trumpeter and jazz education pioneer Herb Pomeroy passed away on August 11. | |

| Photo by Bob Kramer |

The august, tousled eminence of Berklee College of Music has cased his flugelhorn, stepped off the podium, shut the classroom door, and passed into the night. Irving Herbert Pomeroy III '52, mentor and musician who helped put Berklee College on the world music map, died August 11 after a bout with cancer. He was 77.

As faculty legends go, Pomeroy was, as his idol Duke Ellington once said, "beyond category." During 40 years on Berklee's faculty, Pomeroy became a beloved and revered teacher while building a reputation as a discerning and canny listener, a feisty bandleader, and a trumpeter who could play anything from bop to Duke to the Ice Capades. He made numerous albums as a bandleader and dozens of recordings as coleader and sideman, including sessions with Charlie Parker and Charlie Mariano.

"Music is a glorious life," he said in interview two years ago, "because of the richness of the music and the wonderful people. The glory of the music keeps you going." In that interview, Pomeroy sidestepped the spotlight and shone it on the classroom genius of his Berklee colleagues John LaPorta and Joe Viola. These three musicians virtually invented formalized jazz education. After seeing Louis Armstrong on film, Pomeroy took to the trumpet, evading his family's legacy of Harvard and dentistry. He spent nights during his freshman year at Harvard sitting in at Boston's jazz clubs before transferring to Schillinger House (now Berklee) for five semesters. Afterward, between 1953 and 1955, Pomeroy endured grueling months-long road stints with the big bands of Lionel Hampton and Stan Kenton and the Serge Chaloff Sextet.

In 1955, Pomeroy joined the Berklee faculty full time, where he developed classes in line writing, arranging, and Ellingtonian orchestration that gradually elevated his reputation as one of the great jazz teachers. Gracious manner, mental acuity, and dry wit characterized his classroom style over the course of 93 consecutive semesters. For years, Pomeroy would teach mornings at Berklee, play matinees at the Colonial Theatre, zip over to MIT for early evening classes, grab a sandwich, then go back to the Colonial. Around midnight he'd go home to stacks of band contracts (some 50 gigs a year) and student charts. "How'd I do it?" he asked with a chuckle. "Today I'd need a nap." Nonetheless, Pomeroy found the energy late in life to coach ensembles at New England Conservatory-likely more for love than money.

Pomeroy's appreciation for, and intimate study of, Duke Ellington's music informed much of his classroom work and helped raise scores of talented musicians, including the late producer Arif Mardin '61, The Simpsons composer Alf Clausen '66, composers and arrangers Alan Broadbent '69 and Rob Mounsey '75, vibraphonist Gary Burton '62, late keyboardist Joe Zawinul '59, bassist Abe Laboriel '72, film composers Mike Gibbs '63 and Alan Silvestri '70, to name a few.

Regarding Pomeroy's legendary ears, Professor Jeff Friedman '79 recalls the instructor's 30 rules for voicing as complex and challenging. "Herb may not have known this, but a few of us tried to write voicings that followed all of his protocols, but were 'out' enough that he'd have to go to the piano to figure them out. Stumping him was a triumph for us."

When rehearsing a band for the first time, he'd size up players' strengths and weaknesses. With his uncanny psychological powers, he'd effortlessly goad students and pros to achieve over-the-top results. Seasoned players in an orchestra never sounded better than under Pomeroy's leadership. "Thirty years later," says Pat LaBarbera '67, "I'm still absorbing and applying his technical genius."

During a lull in a composition class, when students asked Pomeroy to talk about conducting, he focused on psychology and strategy rather than technical issues. "If a guy's out of tune, don't tell him to tune up; have the section hold a chord they all can hear, and he'll fix it himself," he told the class.

Pomeroy relished the intimacy of playing with small groups. "He was keen on interacting with the piano," says Pomeroy's longtime pianist Professor Paul Schmeling '63. "If I played a different chord, he'd react immediately, analyze later. He appreciated pianists who went beyond fake-book changes. He'd say, 'Give me those chords when I play!'"

Herb's former students gave him a well-deserved tribute upon his retirement in April 1995, at a Berklee Performance Center concert. A month later, he received a Berklee honorary doctorate of music. During retirement, Pomeroy decided to play more with small ensembles. He performed in clubs and on recordings with Donna Byrne, Mark Kross, and Anthony Weller, as well as with his own small group. But the lure of the classroom proved too strong, and soon he was back at Berklee, teaching master classes and ensembles, influencing yet another generation of up-and-coming musicians.

A public memorial service celebrating Herb Pomeroy's life and music on September 9 at Emmanuel Church in Boston drew musicians worldwide. Greg Hopkins served as the bandleader and Reverend Mark Harvey, a trumpeter and the MIT music director, presided in his low-key way. Hopkins straw-bossed several stunning sets of music, including small-band bop and arrangements from Pomeroy's orchestras, including an Ellington/Strayhorn medley.

Pomeroy's daughter Perry took the mic and enumerated her dad's many Ellingtonian qualities, such as an unwavering commitment to what he believed in, an uncanny ability to make people feel important, and his uncompromising honesty with others and with himself. Jazz vocalist Rebecca Parris summed up the sentiments of many at the tribute, saying, "We've lost a huge piece of friendship in our lives."

Next spring, tribute concerts are planned at MIT and Berklee. For more information on Pomeroy or to contribute to a Berklee scholarship in his name, visit www.berklee.edu/giving.