Berklee Today

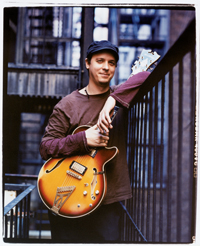

Kurt Rosenwinkel '90 stands tall among a crop of young jazz musicians who are breaking new ground.

|

|

| Photo by Lourdes Delgado |

Rosenwinkel was introduced to international jazz audiences through his tours and recordings with Paul Motian, Gary Burton, Joshua Redman, and others in the early 1990s, and he has since built his own career as a headliner.

After leaving Berklee in 1991 to tour with Burton's band, Rosenwinkel relocated to New York. He became a pivotal figure in a coterie of rising young jazz musicians that included pianist Brad Mehldau; saxophonists Myron Walden, Mark Turner '90, Seamus Blake '92, and Chris Cheek '91; bassists Matt Penman '95, Omer Avital, and Ben Street '88; drummers Jeff Ballard and Jorge Rossy '90; and others. They established their careers collectively during the 1990s playing an adventurous brand of jazz in various configurations in New York clubs and on recordings for the prolific Fresh Sound New Talent label. Mitchell Borden's legendary nightspot Smalls Club in Greenwich Village became the proving ground for Rosenwinkel and company. Smalls provided a forum for Rosenwinkel to explore his ideas, develop his artistic identity, and begin attracting an audience.

Rosenwinkel grew up in Philadelphia, the son of parents who both played the piano and listened to a variety of music around the house. While Rosenwinkel's music reveals traces of the musical influence of others (then again, whose doesn't?), his style is virtuosic and absolutely distinctive. Some critics have compared his harmonically complex compositions to those of Wayne Shorter. As far as his guitar playing goes, the torrent of eighth notes that Rosenwinkel is wont to unleash in up-tempo, bop-oriented solos may occasionally recall those of fellow Philadelphia fret master Pat Martino. At other times, Rosenwinkel's slurred-note approach evokes the smooth lyricism of Metheny or the intervallic probing of Scofield.

Rosenwinkel has his own unique identity, though, both as a guitarist and composer. A trademark of his sound is the blend of his clear guitar tone with his subtle, wordless vocalizing. Singing each note he improvises through a lapel mic fed into his amp creates a wide, legato sonority that is instantly appealing and even otherworldly at times.

I caught Rosenwinkel's set on a warm summer night at the Fat Cat in the Village. He and bassist Ben Street were exploring South American grooves with celebrated Brazilian musicians Toninho Horta (guitar and vocals) and Robertinho Silva (drums) to a packed house. While most of Rosenwinkel's recorded output lies within the broad parameters of contemporary jazz, the Fat Cat set suggests his openness to other avenues of expression. Now that Rosenwinkel has left Verve, he plans to explore other possibilities on his own label and through tracks that will be available only at his website (www.kurtrosenwinkel.com). Rosenwinkel has proven that even in the populous field of jazz guitar, a new voice with something compelling to say will be heard.

|

|

| Photo by Lourdes Delgado |

I began playing piano when I was nine and picked up the guitar when I was 12 and played both from the age of 12 on. By the time I got to high school, I knew I wanted to go to Berklee, and I thought I should choose one instrument to focus on. I had taken guitar lessons the whole time but I'd only taken piano lessons at the beginning. To help make the choice, I decided to take a year of jazz-piano lessons and see where I was with that. I studied with a great pianist and teacher in Philadelphia, Jimmy Amadie. In the end, I chose guitar because I felt I was better at guitar than piano. I had gotten farther with it and developed something on the guitar. Sometimes I regret the choice. [He smiles.] In some ways, the piano is a more natural instrument to me. It's easier to get pleasing sounds out of the piano. Guitar is like a trumpet. You have to stay on top of your practicing and technique. It requires a lot of discipline to keep from making mistakes all the time.

Do you think that's because it takes two hands to produce the notes on a guitar?

Yeah, and the hands do completely different things. Guitar playing is counterintuitive. The piano or the drums are very direct. There's one action to make a sound. Guitar is a very incredible instrument. It's deep. The musical ideas that come from the guitar itself don't sound like anything that comes out of another instrument. The sounds can be so interesting and peculiar sometimes.

What attracted you to jazz when you were in your formative years?

My dad played Erroll Garner-style piano-very free and improvisational. He'd go off on tangents. My mom didn't play that much when I was growing up, but she had trained to be a concert pianist. Although she'd put it down for a number of years, she was always listening to music. I heard a lot of different music around the house and on the radio. WRTI-FM in Philadelphia is a great jazz station. Every night when I was going to bed, I'd put it on and listen. They played Coltrane, Eric Dolphy, and avant-garde jazz in the late hours.

So the more adventurous jazz artists were those who caught your ear?

Yeah, I was really into the idea of free improvisation, or conceptual approaches to music. My mother took me to a concert by the Ganelin Trio, a Russian avant-garde piano trio. It was superb, one of the best concerts that I've ever seen. It made a deep impression on me. The musicians were doing things like hitting the inside of the piano to make different sounds, and I really loved it.

"The Cross"

|

||

|

A Look at Rosenwinkel's Style By Mark Small The forthcoming book from Mel Bay Publications, Kurt Rosenwinkel Book of Compositions, contains 14 pieces by the guitarist and seven guitar solo transcriptions, providing a glimpse of Rosenwinkel's approach to composition and improvisation. "The Cross," from Rosenwinkel's Deep Song CD (Verve B0003928-02), is provided on page 14 in lead sheet format and with a transcription of Rosenwinkel's solo courtesy of Mel Bay Publications. The track may be heard here courtesy of the Verve Music Group. "The Cross" begins with a 30-second Latin-flavored vamp in 3/4 played by bassist Larry Grenadier and drummer Jeff Ballard. Pianist Brad Mehldau enters a few bars before Joshua Redman and Rosenwinkel play the melody together. For this tune, Rosenwinkel has constructed alternating long and short sections. For sections A and C, Rosenwinkel wrote chord progressions (four and six bars in length, respectively) that are played four times each. The shorter B and D sections are more harmonically active. Some of the chord types in these sections go beyond the harmonic language typically found in standards. Of note are the minor-seventh chords with the flatted-sixth degree and his use of the inversions Ab/C and E/Ab (the latter is the enharmonic equivalent of an E chord with the third in the bass). As well, the root motions of the chords depart from traditional jazz practices. Of his writing process, Rosenwinkel says, "I play until I find something that I can develop. It usually starts with a chord progression. Some of the things that end up in my music can't be accurately described with chord symbols. It's about the voice leading from one specific voicing to another. Some times chord symbols can't really represent what's going on." For the structure of the solo sections, Rosenwinkel gives Redman and himself room to stretch out. The A section is expanded to 90 bars of C to g minor. Rosenwinkel also simplified the chord progression of the D section and created a repeating four-bar vamp from the first four chords. The chord progressions for sections B and C are the same as those in the head. Regarding note choices in his solo, Rosenwinkel plays inside and outside the C to g minor vamp, adding more chromatic notes after bar 36. He digs into the changes pretty consistently in sections B and D. Guitaristically, Rosenwinkel is comfortable articulating the notes with the pick and adding slurs and glissandos for variety. "When I practice, I pick every note so that I will be able to do that if I want to," he says. For inflection and phrasing in my solos, I'll do a mixture of both." Throughout, the solo, Rosenwinkel plays with control, rhythmic agility, and a sensibility for shaping his lines and the overall contour of his solo.

|

||

I had The Real Book and started learning standards. There was a club in Philly called the Blue Note. It wasn't affiliated with the other Blue Note clubs. But I would go there for jam sessions every Monday and play the tunes I'd learned. The players were older cats, and I felt I was making contact with the real aural tradition of jazz. I'd call a tune, and they would come up with an instant arrangement. They had all these ideas that were a revelation to me. All I'd gotten from The Real Book were the melody and chord changes.

Now, when I want to learn a song, I'll try to find a vocal version with strings or a big-band version and see what the arrangers did to the tune. I like to learn from the history and tradition of the song. That will teach you a lot about the jazz tradition, and you can bring those ideas into your own version of the tune.

At a young age, were you feeling inclined to become a jazz musician?

I knew I wanted to be a musician, but I wasn't thinking about being a jazz musician at first. When I was eight years old, I liked Kiss and wanted to be a rock star. That was just a youthful thought. But I was as certain then as I am now that I wanted a career in music. I was really lucky to know without any doubt from the very beginning that I was going to be a musician.

What did you come to Berklee to study?

I didn't have anything in particular in mind. A lot of my musician friends in Philadelphia were going to Berklee, and I followed in their tracks. I wanted to go to a school where there were a lot of people doing what I wanted to do. At Berklee, I would go down to the ensemble rooms with my amp on a cart and listen to the bands in the practice rooms. If something sounded cool, I'd ask if I could hang out or play. I'd do that maybe six hours on the weekdays and 12 hours on the weekend. Playing all the time was a valuable part of being at Berklee.

I wasn't too focused on the academic work back then, but I had some very good courses. Ed Tomassi's "Chord Scale Voicings for Arranging" was great for me. I had some excellent harmony classes too. I liked the Berklee approach to harmonic analysis.

You left Berklee to accept a gig with Gary Burton's band. How was it that he became aware of you?

Larry Grenadier and a few other friends who were playing in Gary's band recommended me. After [guitarist] Wolfgang Muthspiel ['90] left the band in 1991, I did an audition with Gary and got the gig. I remember going home and finding messages for gigs on my answering machine from both Gary and Paul Motian. That blew my mind.

When you left Boston to relocate to New York, did you know many people there?

There was an exodus of my musician friends who left Boston and went to New York. I moved down here with Ben Street and Jim Black ['90], and Jon Dryden ['91]. We lived in a house together and played a lot of sessions. It took about a year for me to really meet people from the New York scene. It was hard to make contact. If you played a session, you might meet a new person who would call you a month later for another session, and you'd meet more players there.

New York is expensive. Were you getting enough gigs to make ends meet at first?

Actually, that was the period of time when I was playing with Gary's band and with Paul Motian's band, so I was making money on the road. It was a perfect transition. After I'd been in New York for a year, I quit Gary's band and went to Spain for five months. I wanted to clear my head. When I came back at the end of 1993, I began playing at Smalls in the Village. Ben Street, Jeff Ballard, and I had been playing together since I moved to New York. Jeff was given a regular Tuesday night gig at Smalls by Mitchell Borden, and Jeff asked Ben and me to play there with him. We played at Smalls every Tuesday night for five or six years.

It was a struggle to get by at that point. For years I was pulling the cushions off the sofa to see if I could find some change to buy a slice of pizza. John Scofield has always been one of my big supporters. He and his wife, Susan, were really good to me. Back then they were helping me shop a record I'd made and knew money was tight for me. Once, Susan just sent me a check and wrote on it, "Pizza money." That was really warm.

How did you become connected with Fresh Sound New Talent Records?

I'd met Jordi Pujol [Fresh Sound's owner] through [drummer] Jorge Rossy. Jordi had asked Jorge to help him find new musicians. When Jorge became the A&R man for Fresh Sound, he did a record with Brad Mehldau, with whom he'd been playing. Later, I did a record, and soon a lot of players I knew were recording for the label. I played on about a dozen CDs for Jordi. It was a great opportunity to record, and it helped financially. It gave a lot of us a medium in which to manifest our ideas as artists and formulate concepts.

Did you ever think it was a daunting prospect to develop your own identity as a jazz guitarist amongst influential players such as Pat Metheny, John Scofield, Mike Stern, and so many others who are so very well known in the field?

I never had to grapple with that issue, but I know a lot of people do. What helped me in that regard is that I have always written music. That has helped to define my style. I don't have an agenda when I write. The songs come out and are what they are. And then I have to learn to play them. They're written at a level that's beyond my abilities as a player. Composing has been an important teacher for me. My songs have forced me to grow as a player and helped me develop my style. When you're writing, what you hear is not limited by what you can play. If people thought about it, they'd realize that they can hear beyond their abilities on their instrument.

Your angular melodies and harmonically rich chord choices indicate that you must work a lot on the harmonic intricacies of the guitar.

I do. I love harmony. I've had to work really hard to be able produce these sounds on the guitar. I want to be free to improvise with the harmonic language I am dealing with in my tunes. I play a lot with [saxophonist] Mark Turner, and the harmonic content of his songs is really sophisticated. His songs force me to come to terms with the intricacies of my instrument and make music with the songs. I work a lot on the instrument to become conversant with the harmonies. I don't want to be thinking about scales and chords when I'm playing. I want those to be second nature so that all I'm thinking about is melody.

Does singing along with your improvisations help you to keep things melodic?

It keeps me in touch with the primary impulse of music: to sing. I imagine that's where music started.

When did you start using a Lavalier lapel mic to capture the sound of your singing?

When we were developing our sound at those weekly gigs at Smalls, people would come up and ask me if I was using a chorus effect on my guitar. I would tell them I was just using a delay and some reverb, and they'd walk away puzzled over how I was getting my sound. I didn't realize how much the singing was part of my sound until I started recording. The engineer would usually just put a mic in front of the amp, and I'd come away from the studio feeling that there was a big part of my sound that hadn't been captured. I finally figured out that my voice was creating the effect that people at the club were asking me about. I realized that in the studio they should record my voice, too. Once we started doing that, I got what I recognized as my sound.

From that point on, I started to pay more attention to it and develop it. At first I had a mic on a stand setup in front of me, but that made me self-conscious. I hated having a mic in my face. It called too much attention to what I was doing, because it's a subtle thing. Then I had the revelation to get a Lavalier mic that would be out of the way and inconspicuous.

The blend of the singing with your guitar lines gives the notes a bit more sustain.

It also solves the problem of balancing the notes within a chord. When I play a chord and realize that one note of the chord didn't come out as loud as I wanted it to, I can sing it. This enables me to react and balance the harmony, whether it is an inner voice or the melody at the top of the chord.

Will the music you've been playing with Brazilian guitarist Toninho Horta become a recording at some point?

We are discussing that, but for now it is just a tour with a week at the Village Vanguard, gigs in Japan, and a few West Coast dates. I have been a fan of Toninho for years. My manager Anders suggested that we work together. In some ways, what Toninho does has parallels to my music. He also sings along with his playing, but in a different way than I do. I love what he does. We've been playing tunes by Milton Nascimento, some of Toninho's, and some of mine.

Since you and your family now live in Switzerland, do you feel a little removed from the New York jazz scene?

I felt like getting out of New York after living there for 13 years. My wife is Swiss. We came back and forth for a while when she was in school, but I wanted new information in my overall life scene, and I just decided to move. First Rebecca and I moved to Zurich, and our older son Silas was born there, he's now two years old. Our second son, Ezra, was born last June. Now we live in Lucerne, and I teach at a music school there a few days a week when I'm in town. The schedule is very flexible so that I can do my tours. We have a garden, and everything is very peaceful there, with the view of the mountains. When I'm home, I become a recluse. When I come back to New York, I get an influx of energy.

I understand that you have now left the Verve record label.

Verve was great for me. They helped me get established and build an audience, and I'm proud of the four albums I made for them. I'm independent now. My manager Anders and I are starting a new label. This time, I'm going to make all the money. The first release will be a live album I recorded last January with my quintet at the Village Vanguard. That will be released in March of 2007. We will have a distributor to get the CD into the stores, and it will be available through iTunes. We are taking care to launch the whole thing correctly.

I have a home studio and I'm planning to do another studio project like the Heartcore album. I enjoyed making that record; it was a huge challenge. Except for the mastering, I did it mostly myself-composing, engineering, mixing. Heartcore was very different from anything in my recorded output. I wanted to do it because I had been doing things like that my whole life. I would make tunes that were completely free in my home studio-my laboratory. Along the way, a lot of cool songs have come out that didn't fit with the music I played with my band. They were oddities.

My website will be upgraded so that I can sell downloads. I want to be able to upload songs I create in my studio that don't have anything to do with what I do live. For instance, I've recorded a rock song that's very dark. I'm singing lyrics on it and showing my David Bowie roots. I want to have an outlet for these things. I'll upload them, and people can buy them for a buck.

What else do you foresee in your future?

I look forward to developing my group and making a record with Toninho Horta and making Heartcore II. I'd also like to do a solo guitar record someday and an album of the songs with lyrics that I write. I'd also like to do an orchestrated project with a larger group. Right now, though, I'm really where I want to be.