Lost John Coltrane Record Still Sounds Like Freedom

John Coltrane

Image by Hugo van Gelderen (Anefo)/Wikimedia Commons

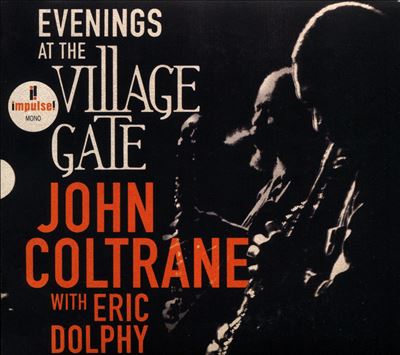

Evenings at the Village Gate: John Coltrane with Eric Dolphy was released this month on Impulse Records.

A fresh John Coltrane release, Evenings at the Village Gate: John Coltrane (with Eric Dolphy), emerged this summer like a time capsule from 1961. Discovered in the New York Public Library archives, this live recording captures the powerful collaboration between saxophonist John Coltrane and woodwind player Eric Dolphy, unfairly maligned by some critics of its day as "anti-jazz."

In honor of this rare opportunity to hear a new Coltrane album in the 21st century, we spoke with ethnomusicologist Emmett G. Price III, dean of Africana Studies at Berklee. Price's fascination with Coltrane dates back to his undergraduate days and the publication of his first academic article, "The Development of John Coltrane's Concept of Spirituality and Its Expression in Music." In this interview, he sheds light on the musical and cultural significance of this long-lost recording.

How do you approach this newly unearthed set of recordings as an ethnomusicologist?

As an ethnomusicologist, I am geeked! Richard Alderson was the engineer at the Village Gate in 1961. The 24-year-old often experimented with the state-of-the-art sound system and recorded parts of Coltrane’s residency. Alderson would go on to engineer recordings for Nina Simone, Thelonious Monk, Sun Ra, Roberta Flack, Grover Washington Jr., Bill Withers, David Sanborn, Muddy Waters, and numerous others, including Bob Dylan. This recording was discovered by a Bob Dylan archivist at the New York Public Library.

Evenings at the Village Gate not only gives us a glimpse at what Coltrane and Dolphy were working on musically, but also a perspective on their relationship. Dolphy has a lot to say (musically) as part of Coltrane’s band. Absolutely fascinating!

During the summer of 1961 the Civil Rights Movement was gaining momentum with protests, sit-ins, boycotts, and freedom rides. Within this context, Evenings at the Village Gate offers another example of the power of courageous musicians to inspire hope, innovation, and empowerment through sound.

—

Around the time of this recording, the seemingly chaotic music Coltrane and Dolphy's quintet was performing was criticized by a DownBeat writer as "anti-jazz." What made this music so controversial in the jazz scene during its time?

I do not hear chaos. I hear courage, honesty, transparency, brilliance, pain, trauma, and many other feelings and emotions, but not chaos. Coltrane played with a definitive sense of precision. The whole idea of “sheets of sound” is a reference to his deliberate approach to improvisation. Dolphy was known to hold conversations with birds during his practice sessions in Los Angeles.

When [critics] John Tynan, Leonard Feather, and others disparaged Coltrane, Dolphy, Ornette Coleman, and others with the label “anti-jazz,” it was a reflection of the arrogance of perceived superiority. Coltrane and Dolphy were not controversial, they were two liberated Black men inspiring others to the same liberation. Their sound unleashed hope in the midst of suffering and invoked the sounds of ancestors while calling forth the empowerment of generations to come.

Bring us up to the present: What do you think is the cultural or historical legacy of a new Coltrane recording in 2023? Why should people listen to these recordings, and what should they listen for?

Coltrane was a guru. Any new writings, recordings or even photographs help us to learn more about one of the most impactful and influential creatives in the history of humanity. During the summer of 1961 the Civil Rights Movement was gaining momentum with protests, sit-ins, boycotts, and freedom rides.

Within this context, Evenings at the Village Gate offers another example of the power of courageous musicians to inspire hope, innovation, and empowerment through sound. From the 15:45-minute version of “My Favorite Things” to the 22:41-minute rendition of “Africa,” we experience Coltrane, Dolphy, Art Davis, Elvin Jones, McCoy Tyner, and Reggie Workman doing their part to make the world a better place for all through the gift of creative expression.

We all know that this word which so many seem to fear today, "Freedom," has a hell of a lot to with this music.

—

In discussing this release with NPR, ensemble bassist Reggie Workman said Coltrane "was growing into a place where he did not want to be inhibited by the steps and the changes that were prescribed by certain structures. . . . He wanted us to be about a chant." What do you take this to mean?

The word “chant” means to sing or intone. Coltrane challenged his band to find their inner “personal” voice and free it by singing or intoning without boundary, stricture, or inhibition. He challenged them to embrace their mind, body, and spirit while exploring, examining, and engaging the creative process beyond any self-imposed limitations.

In a June 2, 1962 letter to DownBeat's editor, Don DeMichael, Coltrane responded to critiques and assertions of “anti-jazz” by stating, “Any music which could grow and propagate itself as our music has, must have a hell of an affirmative belief inherent in it. Any person who claims to doubt this, or claims to believe that the exponents of our music of freedom are not guided by this same entity, is either prejudiced, musically sterile, just plain stupid or scheming. Believe me, Don, we all know that this word which so many seem to fear today, ‘Freedom,’ has a hell of a lot to with this music.”

Listen to "Impressions" from Evenings at the Village Gate: John Coltrane with Eric Dolphy: