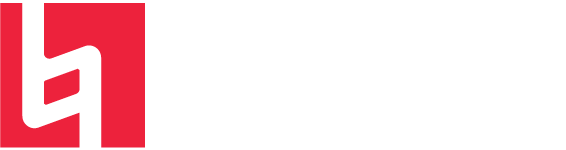

Phil Wilson: The Focus on Emotion

Phil Wilson directs a Rainbow Band rehearsal.

Photo Liz Linder

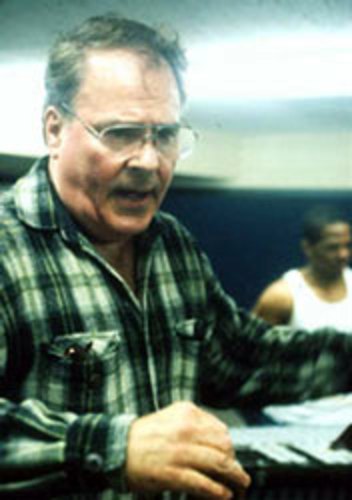

Trombonist Steve Turre (left) and Phil Wilson strategize during a rehearsal at Berklee in 1996.

The Rainbow Band runs through a chart.

Photo Liz Linder

As the members of Phil Wilson's Rainbow Band gather for rehearsal, each musician walks into the room carrying not only a different instrument, but a different accent as well. There's an Italian pianist, a Spanish drummer, a Japanese trombonist, and a Danish vibraphonist. The group's cacophonic warm-up increases in volume with each new entrant while Wilson pulls music charts out of his overstuffed leather briefcase and drops them onto stands in front of each musician. He's shouting instructions over the din, occasionally erupting into a full-body guffaw, and looking quite content to be a man charged with the responsibility of turning mayhem into music.

Slithering through the smorgasbord of sound comes hints of the melody of "Giant Steps." Two saxophone players catch each others' eyes as they realize they have simultaneously stumbled on the Coltrane standard that every jazz student works to master. Within moments, most of the band joins in though the tune is not currently in the Rainbow Band's repertoire.

Wilson waves his right arm in the air to begin the rehearsal, but the band presses on with the melody. He waves both arms in the air and everyone quiets down except for the two saxophonists, quietly trying to get to the end of the 32-bar form.

"Hey!" Wilson yells. Now the room is quiet. "The song . . . has . . . ended," he says sternly. Every musician knows enough English to discern the bandleader's message: Phil Wilson is running this band, and it's time to get to work.

Working with a diverse crop of students has long been Wilson's calling card at Berklee. He was brought to Berklee in 1965 to be its trombone guru, and shortly after his arrival, started a renegade after-hours ensemble that met in his office, sometimes practiced in the dark, and for some reason, always seemed to attract large numbers of international students. The group also became home to some of the best players in school. Among Wilson's former student band members are Cyrus Chestnut '85, John Scofield '73, Ernie Watts '66, Terri Lyne Carrington '83, Bill Pierce '73, Roy Hargrove '89, and the Mighty Mighty Bosstones' Dennis Brockenborough '91.

After originally dubbing the group Thursday Night Dues Band, Wilson changed its name to the Rainbow Band in 1985.The group performed its 35th anniversary concert at the Berklee Performance Center on December 5.

"Music is something that borders of countries can't contain," says Wilson, who has led the band on trips to Barbados, France, Guyana, the Dominican Republic, Surinam, El Salvador, and Honduras.

In similar fashion, the Rainbow Band's repertoire, though rooted in jazz, often travels beyond typical boundaries of music. In recent performances, the group has moved from gospel to world music, and has taken on the work of composers as diverse as Jerome Kern, Stevie Wonder, and Nicolas Sorin, a 21-year-old Argentinian Jazz Composition major.

"Selection of music is tremendously important," Wilson says. "I always play to the strength of the players. Sometimes you find strengths in players you're not aware of at first, and you try to bring them out."

Regardless of what talents individual students posess, Wilson always emphasizes two particular aspects of being a performing musician: emotion and focus.

"I talk a lot about the emotional content of what they are doing," Wilson says. "I want them to think about how they're playing the notes. It's about their attitude, whether they're having fun or not."

"One of the biggest problems musicians run into is difficulty focusing. You have to be able to focus on reading your part, but you also have to keep in mind the harmonic framework of the tune and see the piece as a whole. You need focus so you can go on automatic. Sometimes I'll stop a student and say, 'Just where is your mind?' You'd be amazed at the answers I get."

The rehearsal room is silent as Wilson shuffles charts on his stand. "Why don't we warm up with 'Kilgore Trout,'" he says. "Yeah, right, warm up," one of the band members says with a smile, knowing that the tune is one of the most difficult they're working on. Keyboardist Lyle Mays wrote "Kilgore Trout" when he was Wilson's student in the early 1970s. It is a particularly tricky tune for the horn players, as it features a complex melody and equally challenging background lines.

"One, two, uh-uh-uh-uh," Wilson counts, and the rhythm section begins a vamp that serves as an introduction to the tune. Moments after the saxophones and brass enter, Wilson waves the band to silence. "You were a little off there, Kenzoku," he says to the trombone player. "It's like this." Wilson explains what he's looking for by clapping on the second and fourth beats of each measure while singing the rhythm. The trombone player nods his head and then plays the phrase exactly how Wilson has just sung it. "Yeah, babe," Wilson says. He'll deliver the two words quietly or with great gusto, depending on the circumstances, but it's always a clear indication that he's happy with what he's just heard.

"Okay, let's try it again."

The biggest obstacle that Phil Wilson had to overcome in his own musical apprenticeship stemmed from a physical problem. A piano teacher discovered that Wilson, at the age of 10, had dyslexia, a reading impairment that was causing him problems at school and during music lessons. Wilson had been studying piano since he was four, but came to realize that he was depending on his ears almost exclusively.

"My teacher noticed that I couldn't see blocks of notes, and she suggested that I take up a single-line instrument," Wilson says. He soon picked up the trombone and became proficient enough to land a job at 15 with the Ted Herbert Band, a group based near his home in Belmont, Mass.

Herbert loved Wilson's playing, but he didn't know the teenaged trombonist was learning most of the music by ear. During rehearsal one day, the bandleader asked Wilson to play a particular riff from a tune. He played the same riff he had been playing all along, but it differed from the written melody. His suspicions confirmed, Herbert fired Wilson.

"The embarrassment was mortifying," Wilson says. "It forced me to find a way. I worked and got an ability to focus. I forced myself to turn my ears off the first two times through and just focus on reading. It was my own way of figuring out how to deal with it."

Wilson has been dealing quite nicely ever since. He left New England Conservatory after two years to go on the road with the Dorsey Brothers Orchestra, and later played with Woody Herman, Louis Armstrong, Louis Bellson, Clark Terry, Buddy Rich, and Herbie Hancock. Several bandleaders hired him as a composer and arranger, and he won a Grammy Award nomination in 1969 for his arrangement of "Mercy, Mercy, Mercy," as recorded by the Buddy Rich Big Band.

The international character of Wilson's life at Berklee has also found its way into his own projects. He recorded two recent records, his 11th and 13th as a leader, with the Hamburg, Germany-based NDR Big Band. On Pal Joey Suite (Capri, 2000), Wilson reworks Rodgers and Hart songs from the popular Broadway show, which opened in 1940. On his prior NDR-backed record, The Wizard of Oz Suite, (Capri, 1993), Wilson creatively refashions the Harold Arlen songbook that scored the 1939 film.

His composition, arranging, and teaching talents notwithstanding, it is perhaps Wilson's trombone sound that most strikes people who go to his concerts. Writing for the Boston Herald in 1993, music journalist Harvey Pekar described Wilson's playing as "lush" with a "well-controlled vibrato, lyricism, incredible high note playing," and "fresh and unusual" melodic lines.

Wilson's trademark sound on his instrument has turned out to be one of his most valuable teaching tools.

"You've got to make students aware of the sound, how important it is, and you do that by being an example yourself," Wilson says. "You can tell my sound from other trombone players, and you can't miss it if you hear it week after week."

While Wilson demands that each of his private students work on what he calls "trombone aerobics," he also pushes them to develop muscles for musical creativity, chiefly by having them write a 32-bar composition every week.

"Sometimes they won't be able to control the horn enough to show melodic ability," Wilson says. "But when they have time to write it out, you can see what's going on melodically and harmonically in their heads. It can also really help them gain confidence."

When saxophonist Bill Pierce was a skinny teenager in the early 1970s, long before he joined Art Blakey's Jazz Messengers or became Berklee's Woodwind Chair, he thought of himself as one of the "worst guys" in Wilson's Dues Band.

"Phil was the first guy to give me the opportunity to do anything," Pierce said during an 1995 interview before a concert he and other alumni gave in tribute to Wilson. "I didn't know anything,but I guess he heard something in me that he really wanted to do something with, to see if I could do something with it, and I'm really grateful for that."

Back in the rehearsal room, Wilson is urging on the next generation of jazz messengers. On the third try, the band successfully twists its way through the head of "Kilgore Trout," and now players are taking turns standing and soloing. As his trombone player begins his improvisation, Wilson also stands, listening intently and keeping time with his entire body, moving his head from left to right, chopping his left arm through the air, and stamping his feet. As the solo nears its end, a large grin settles on Wilson's face and he yells out those words of clear affirmation:

"Yeah Babe!"

From Toots to Debussy: Phil's Favorites

- Bill Evans with Toots Thielemans, "Affinity"

- Duke Ellington: "Such Sweet Thunder," Far East Suite," and "Harlem Suite"

- Miles Davis, "Porgy and Bess"

- Louis Armstrong, "Satchmo at Symphony Hall"

- Almost anything by J.S. Bach, Debussy, Ravel, Oscar Peterson Trio, and the Nat Cole Trio