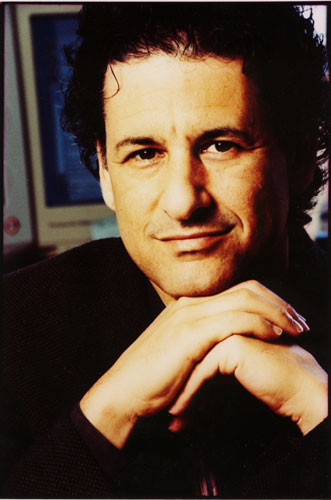

Alumni Profile: Daniel Levitin '80

Daniel Levitin '90 melds his music and science education to inform his work.

Photo by Arsenio Corôa

Levitin recalls the words of his Berklee professor Gary Solt: "You've got enough music in your head. Your job now is to get it into your fingers and into your ears."

Photo by Owen Egan/McGill University

Says Levitin: "The Berklee education is theoretical and practical. It's an intense conservatory environment for contemporary music. I don't know another place its equal."

Photo by Owen Egan/McGill University

You know when you get a song in your head and you can't get it out, humming it all day long? You might not know why, but Daniel Levitin '80 does. The alumnus has consistently and intuitively navigated between science and music. He studied music and psychology at Stanford, but yearned for more of a bona fide music education. That led him to Berklee (where he studied guitar and saxophone and majored in performance), stints in bands, and a career as a music producer/engineer, working with such artists as Santana, Blue Öyster Cult, and the Grateful Dead. Fast forward 10 years and he shifted gears again, earning degrees in cognitive psychology and cognitive science. Today he is a professor of psychology, behavioral neuroscience, and music at McGill University in Montreal.

Enter Levitin's writing career, where he formally synthesized it all. "By 2005, I realized I had been teaching cognitive physical science and I had all those fabulous experiences in the studio. That was a perfect pairing," he says. "A lot of cognitive science can be explained through music. I thought it would be cool to combine these things. All along, I'd been doing this in my teaching. It was a matter of writing down what I do in my classroom lectures."

As a result of his circuitous yet logical path, Levitin proudly wears many hats: cognitive psychologist, neuroscientist, record producer, musician, and writer. Not surprisingly, in the process he's capitalized on one of Berklee's greatest lessons: improvisation. "At Berklee, it's taught as a life skill. You can use it anywhere," he says. "My three careers as producer/engineer, as an academic scientist, and as a writer have been improvisation."

Today Levitin is a household name in the field of musical perception and cognition. He can explain why we're drawn to particular rhythms and not drawn to others, why music is integral to our being, and how many hours of practice are necessary to become an expert musician.

The interrelationship between music and the brain is what drives Levitin's research. From This Is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession to The World in Six Songs: How the Musical Brain Created Human Nature, he's boiled down his scientific findings into digestible prose, whetting the appetite of anyone who's ever tapped a foot to a tune, from music enthusiasts to virtuosos.

He garnered some of his material from his days at Berklee including from his favorite course, an arranging class with former faculty member Gary Solt '76, who also gave him guitar lessons. "A lot of the first two chapters of This Is Your Brain on Music are based on my impression of my understanding of the material from that class," he says. "The beginning of that class was really about theory and harmony. It took me 30 years to synthesize."

A Route of His Own

At Berklee, he learned the importance of being open to a non-linear path. "One thing I learned at Berklee talking to students and faculty, if you want to make a living in the music business, you can as long as you're flexible in the way you do it," he says. "Often you don't get a chance to choose the precise path you take."

Levitin's father underscored this message, warning him to be wary of closing doors. After Berklee, Levitin moved to Oregon and had the chance to play with the Alsea River Band but hesitated because of their country leanings (he wanted to join a rock band). "My father said, 'Don't be so inflexible. Don't be so arrogant. Maybe you can learn something from them.' I took my father's advice and learned about showmanship and performance and strings. I played with them for about a year and my experience was the basis for chapter 4 of The World in Six Songs."

The lesson came again when Levitin moved to San Francisco and auditioned as lead guitar player for a bunch of bands, including the Mortals, which impressed him with its hard-edged power pop and Velvet Underground, Police, Ramones, and Beatles influences. After three, two-hour auditions, he was asked to join the band, but as a bass player. "They wanted a melodic bass player. I was tremendously depressed and knew nothing about bass," says Levitin. "My father recommended again that I be flexible. So I took the job, bought a bass and a bass amp. They were great. I spent two years with them."

It's no surprise that Levitin is still improvising and keeping his path flexible and open. A third book, Foundations of Cognitive Psychology: Core Readings, Second Edition, is due out this fall and he's at work on a fourth. Meanwhile, he's collaborating with such musicians as David Byrne, Bobby McFerrin, Rosanne Cash, Michael Brook, and Rodney Crowell on public performances/talks about music and the brain. He's even doing some comedy writing, and submitting his ideas to the comic strip Bizarro.

Levitin acknowledges that his chops are not what they used to be, but good enough to hold his own. "At Berklee, I was the worst guitar/sax player there and I needed that. You wouldn't get better by playing with people who are worse than you," he says. "It was daunting and intimidating, but it was a kick in the pants. In my time there, I grew enormously as a musician. On average, I had an instrument in my hand six to eight hours a day. Since then, my facility/ability has really dropped, but I'm good enough that I can play with some major artists."

For Levitin, this kind of collaboration and improvisation has been the hallmark of his innovative career and he shows no signs of letting up.